about me

Hi there and thanks for dropping by! I'm Daniel, a researcher in global health and development.

My trajectory has been anything but linear, and over the last decade I have been doing research on obscure mathematical objects called quantum algebras, ran a leadership seminar out of an old leprosy ward in Nepal,

and developed machine learning algorithms to catch insurance fraudsters. Oh, and I almost ended up doing a PhD in neuroeconomics...but more on that below.

I'm a generalist at heart; I enjoy coding and math problems just as much as

reading several books at once and writing about anything that captures my imagination.

Such a temperament often gets in the way of becoming a subject matter expert in any domain, but I like to imagine that it lets me spot patterns and connections that specialists overlook.

If there's a thread connecting all of the above, it's probably just a stubborn commitment to understanding how things actually work, whether that's AI, quantum computing or programs to alleviate global poverty.

And why limit my curiosity to intellectual pursuits?

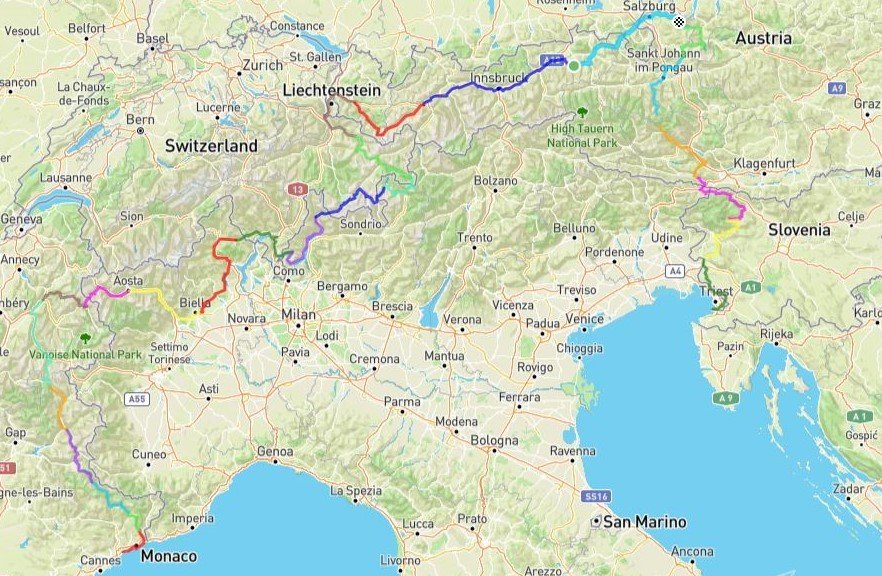

As an avid trail runner & cyclist, I'm always keen to find new ways to explore my limits, some of which I've highlighted below.

And I love connecting these exploits with traveling to new places.

Scroll on to learn more!